L3 Think Smarter, Not Harder: An Introduction to Mental Models

The Myth of Raw Intelligence

- Have you ever watched someone solve a complex problem effortlessly? It often feels like magic. They see solutions where you only see walls. But it is not magic. It is a system.

Most of us try to solve problems using only our raw brainpower. We treat our minds like a muscle that just needs to push harder. That is like trying to build a skyscraper with your bare hands. It does not matter how strong you are; you will fail. Smart decision-makers do not just push. They use leverage. They use tools. We call these tools Mental Models.

What is a Mental Model?

- The mental model is simply a representation of how something works. It is a concept, a framework, or a rule of thumb that you carry in your mind to help you interpret the world.

Think of gravity. You don't need to be a physicist to know that if you drop a glass, it will break. That basic understanding of gravity is a mental model. It allows you to navigate reality without having to calculate the physics of every step you take. The goal of this guide is to move you beyond basic physical models and into strategic models.

Don't be the person with only a hammer.

The Problem with "The Hammer"

- Before we build your toolkit, we must understand why you need one. There is an old saying: "To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail."

If you only look at the world through the lens of one discipline - like economics, psychology, or engineering - you will miss the big picture. You will try to smash complex problems with your one tool. To be a master thinker, you need a Latticework. You need to hang your experiences on a grid of different models. Here are the four essential models to start your collection.

Portrait of Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi (1843), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Model 1: Inversion

- The mathematician Carl Jacobi had a favorite rule for solving difficult problems: "Invert, always invert."

Inversion is the art of thinking backward. Instead of thinking about what you want to achieve, think about what you want to avoid.

Most people ask: "How can I be brilliant at my job?" The Inversion thinker asks: "What would make me absolutely terrible at my job? What would get me fired?"

- Being late.

- Hiding mistakes.

- Being rude to colleagues.

If you simply avoid those three things, you are already ahead of 90% of the population. Solving problems backward often reveals solutions that forward thinking misses. It acts as a filter to remove stupidity before you try to add brilliance.

Practical Application: The Pre-Mortem Before you start your next big project, hold a "Pre-Mortem." Assume the project has already failed spectacularly. Now, work backward to write the story of how it failed. This exercise will expose risks you are currently blind to.

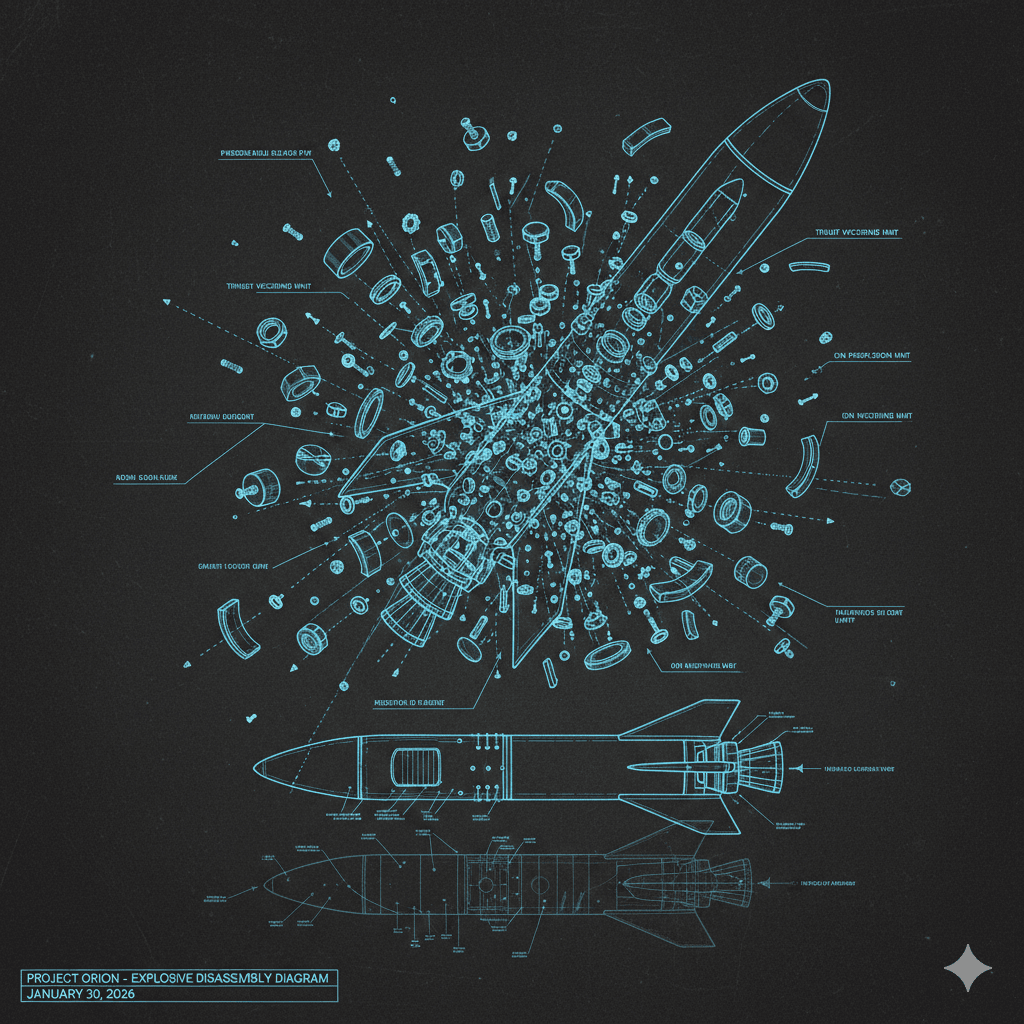

Model 2: First Principles

- This is the tool of the innovator. Most people think by analogy. We look at what others are doing and try to do it slightly better. We say, "I want to build a restaurant like that one, but with better lighting."

First Principles thinking requires you to break a situation down to its absolute truths and rebuild from there. You forget what everyone else is doing.

The Elon Musk Example: When Musk wanted to go to Mars, people said rockets were too expensive. They reasoned by analogy: "Rockets have always been expensive, so they will always be expensive."

Musk used First Principles. He asked: "What is a rocket made of? Aluminum, titanium, copper, carbon fiber. What is the value of those materials on the commodity market?" It turned out the materials were only 2% of the rocket's cost. The rest was inefficiency. By building from the ground up, he cut the price by 10x.

Deconstruction

Model 3: Second-Order Thinking

- In a complex world, every action has a reaction. First-order thinking is looking at the immediate result. Second-order thinking is looking at the result of the result.

The Example:

- First Order: "I am hungry, so I will eat this chocolate cake." (Result: Satisfaction).

- Second Order: "If I eat cake every day, my energy will crash in an hour." (Result: Low productivity).

- Third Order: "If I have low productivity, I will miss my deadline." (Result: Stress).

Smart thinkers do not stop at the first easy answer. They ask: "And then what?"

Model 4: The Map is Not the Territory

- This is a crucial model for the digital age. We often confuse our description of reality with reality itself.

A resume is a map; the employee is the territory. A financial quarter projection is a map; the actual market is the territory.

Maps are useful because they simplify things. But they are flawed. They leave out the potholes, the weather, and the traffic. When your map (your plan/spreadsheet) disagrees with the territory (reality), trust the territory. Do not cling to the paperwork when the building is on fire.

Step 1: Read. You cannot use models you do not know. Read outside your field. If you are an artist, read physics. If you are an engineer, read history.

Step 2: Write. Journaling forces you to articulate your thinking. Write down why you made a decision before you see the outcome.

Building Your Latticework

- Using these models prevents blind spots. They force you to look at a problem from multiple angles. When you layer these models on top of each other, you stop guessing. You start calculating.

You become the person in the room who sees the solution while everyone else is still arguing about the problem. Building your latticework takes time. But the ROI is infinite. Start with these four. Apply them to your next big decision.